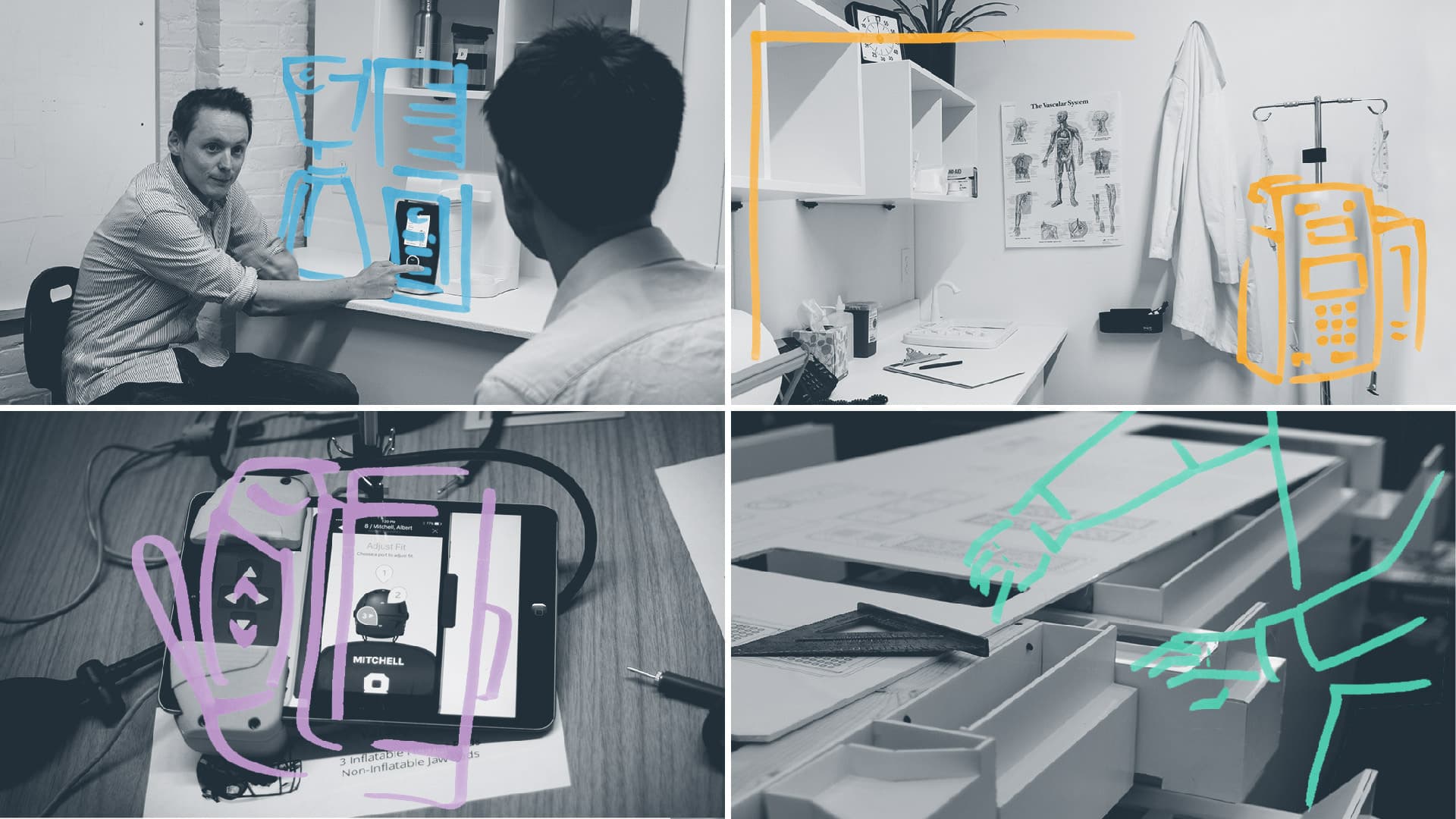

9 Considerations for Planning User Research Prototypes

Prototyping for user research is a major consideration of product development and one that often confuses, because it’s not an exact science. There’s always a question of what to test and when, and there’s no one “right answer.”

9 Considerations for Planning User Research Prototypes

Let's build something together.

Why Sustainability Efforts Stall—And What It Takes to Build Organizations That Deliver

Even the best sustainability initiatives stall when organizational support isn’t there. In this candid conversation, we brought together two perspectives—sustainable product design and organizational transformation—to unpack why most efforts fail and what it takes to build teams and systems that deliver. If you’re running into resistance, this is for you.

Read more

How to Keep Product Development Moving When the Supply Chain Doesn’t

Facing longer lead times or sudden component shortages? This article shares proven ways to keep your development pipeline moving, even when your sourcing strategy hits turbulence. Want a more strategic approach? Download the white paper for a framework to build resilient pipelines that flex under sourcing shocks, shifting regulations, and timeline pressure.

Read more

Design for Manufacturing (DFM): 8 Principles Every Product Designer Should Know

Even great designs fail when manufacturability gets overlooked. Learn eight principles every designer should apply to reduce risk, avoid waste, and ensure your product is ready for real-world production. Need a broader strategy? Download our white paper on building resilient product development pipelines.

Read more

Digital Isn’t a Feature. It’s the Backbone of Connected Product Success.

If you’re building a connected product, this article will help you avoid one of the biggest missteps teams make: treating digital like an add-on. You’ll walk away with a sharper lens on how to design for compliance, adoption, and long-term scalability—starting now, not later.

Read more

Building Resilient Product Pipelines Through Strategic Reshoring

If your product strategy is being tested by supply chain volatility, this article will help you rethink reshoring as a design challenge, not just a sourcing fix. You’ll walk away with a practical lens for evaluating onshoring opportunities, making smarter tradeoffs, and building pipelines that flex under pressure. For a broader framework on designing resilience into your entire product pipeline, download the full white paper.

Read more

Fused Innovation: How Cross-Disciplinary Teams Deliver Smarter Products, Faster

Lessons from my Wisconsin Digital Symposium keynote on building digital systems that actually work.

Read more